Mosman has a number of Sirius placenames – Sirius Cove, Sirius Cove Road, the Sirius memorial near the wharf, but what is the connection of the First Fleet flagship HMS Sirius with Mosman?

HMS Sirius, flagship of the First Fleet, departed Portsmouth on 13th May, 1787, bound for NSW. A naval ship previously named HMS Berwick, she was chosen for the journey due to her storage capacity. She was refurbished and fitted out as an armed store ship, carrying Governor Arthur Phillip, other officers, marines and crew, large amounts of goods and provisions, but no convicts.

Although having been overhauled before departure from England, Sirius leaked badly throughout the journey to NSW, necessitating constant pumping and caulking. On arrival in Sydney Cove the carpenters were busy building housing for the settlement so repairs to the ship had been minimal. Nevertheless, due to dwindling stores in the colony, in October 1788 Sirius was dispatched to the Cape of Good Hope for supplies. This journey took seven months and circumnavigated the globe, still leaking. On her return journey she hit a severe storm while rounding Tasmania, nearly going aground. Sails were ripped, topmasts damaged, the figure head and railings washed away and front sections of the ship badly damaged. On her return to Port Jackson on 9th May 1789, crewman Newton Fowell wrote that she was in such a shattered condition that she was not immediately recognised. Sirius was in serious need of repair.

A convenient cove on the north side of the harbour, about 3 miles from Sydney Cove, was chosen for this purpose, where the crew was less likely to be distracted by bad company. Sirius was towed there on 19th June 1789. Described by seaman Jacob Nagle as Elbow Cove due to its shape, and Captain John Hunter as Careening Cove due to its purpose, this cove later became known as Sirius Cove and eventually Mosman Bay.

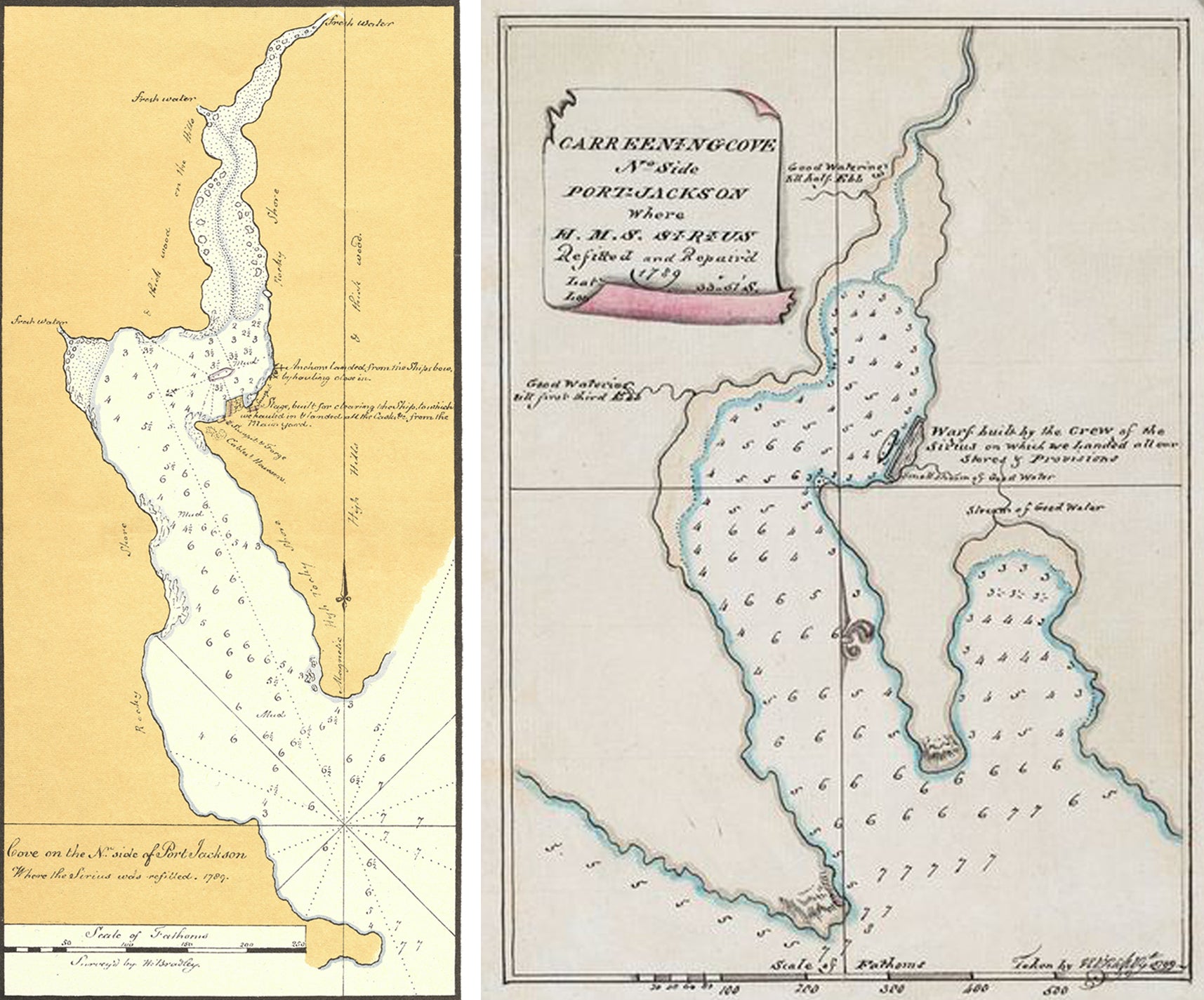

The topography of this cove, clearly shown in Bradley’s Chart #10 (remarkably accurate when compared to a modern map), made it ideal for the purpose of careening the ship. The elbow shape and surrounding high hills shelter the cove from strong winds and large waves, with deep water but also extensive mud flats at low tide. Careening involved positioning the ship at high tide, then causing it to heel over onto its side on the mud as the tide went out so that the hull could be inspected and repaired. (Most of the mud flats were dredged in 1901 to create Reid Park).

The chart shows two sources of fresh water nearby... the waterfalls at the end of the bay (now enclosed and channelled through Reid Park) and a creek on the western side (now the boundary between Mosman and Cremorne). Bradley shows that a wharf, forge and sawpits were built, with the Sirius secured by cables, hawsers and anchors to points around the cove. He noted that anchors, casks and other items had been cleared from the ship and were stored alongside.

Crewman Jacob Nagle recorded that the carpenters built formwork alongside the shore which was filled with rock and made level for a wharf. Here supplies could be landed, and Sirius could be brought alongside in five fathoms of water to enable everything to be removed from her. Once cleared, careening and repairs could begin.

The carpenters found suitable timber on the surrounding wooded slopes and all available crew were involved in the repairs. “Her sides were greatly strengthened with 28 additional riders”, (large timber ribs) strongly bolted inside to the existing timbers to increase their strength. (Southwell). The upper works were strengthened, and broken and rotted planks and rusted bolts replaced. Copper sheath on her hull was removed to examine her bottom, which was quite sound.

During these proceedings, local aborigines were seen watching from the bush, but didn’t visit. Two crewmen went missing. Midshipman Francis Hill had visited Sydney Cove and afterwards been dropped off on the North Shore by boat, intending to walk back to Sirius. When he did not return as expected, parties were sent out to look for him, firing guns to guide him towards help, but he was never found. Gunner’s mate John Mara also got lost when sent to fill water casks near the ship. He had drunk some rum and, before reaching the watercourse, lay down for a rest. On waking after dark he was disoriented and went the wrong way, wandering lost in the bush for several days. Finally his cries were heard from a boat on the harbour and he was rescued.

With few tools or skilled tradesmen, repair of the Sirius took almost 5 months. By the end of October work at Sirius Cove was complete, and the stores and provisions were reloaded on the ship. On 7th Nov 1789, it was towed back to Sydney Cove where some finishing touches were made.

The colony remained desperately short of food, with rations being constantly reduced. By March 1790 the other First Fleet ships had all departed, leaving just the Sirius and Supply in Sydney. It was decided to send Sirius to China for supplies, transferring a number of convicts and marines to the more fertile Norfolk Island on the way. Arriving there on 13th March, the passengers were landed but strong winds and swell prevented mooring, and eventually threw the Sirius onto a reef. Desperate attempts ensured most of the stores were saved, but the ship was soon completely wrecked. The colony’s main lifeline with the outside world was lost, leaving just the tiny Supply.

The 19th March 2020 marks the 230th anniversary of this loss, and Norfolk Island is holding a number of festivities to commemorate the event.

P. Morris. Mosman Historical Society.

Sources: Journals, charts, diaries, letters, memoirs of officers and crew of HMS Sirius: Bradley, Hunter, Fowell, Southwell, Nagle. Details on request.

Photo captions and credits:

Ship similar to Sirius being careened in late 18th century Europe. Wikipedia.

Bradley chart and George Raper chart.

Scale model of First Fleet flagship HMS Sirius.

Bas relief of HMS Sirius at Mosman Bay. Wikipedia.